By Gary Oswald

The coastal people of modern day Liberia and Sierra Leone, especially those who spoke one of the Kru languages, had done well out of the Atlantic Slave Trade. The decline of the Songhai and Mali Empires and then their collapse after the 1590 Moroccan invasion of the Sahel had destabilised the land to their north, destroying existing trade routes and sending refugees down into their territory. As a result they had re-orientated towards the sea, first as fishermen and traders with other Africans, there's some evidence they served as mercenaries in Ghana, and later in terms of trade with the Europeans. They were active slave traders, but more than that they worked aboard slaving ships as sailors, navigators and interpreters, due to their pre-existing knowledge of the coasts. This led them to adopting the "Kru Mark" a distinguishing tattoo that marked them out as freemen rather than slaves, though, despite the name, other unrelated peoples from the same area in the same occupation such as the De also adapted the same tattoos to gain the same protection.

Later those with the Kru Mark would be employed on the British and American ships running anti-slave ship patrols in the Blockade of Africa, providing the same service and thus spreading further throughout West Africa. They would be among the first people employed by the British in Sierra Leone, forming a major source of labour in Freetown, and as the 19th century progressed, they were regularly employed in the Royal Navy and formed a small immigrant community in Liverpool and larger ones in Lagos and Banjul.

Kru itself originally became an ethnic identity based on this labour migration, the Krumen was the name given to Liberians who had left Liberia for work regardless of which language they spoke or their own tribal identities (that is 'Krumen' was the name given to them by Europeans, the name given to them by other Liberians was the rather more caustic 'kobo-tabo' or 'those who suckle off white people'). I'm going to use the word Kru to describe the people from whom the Krumen emerged from now on even those who never left Liberia, as that's the term the Americo-Liberians used, but that's not how they would have identified themselves. There are many Kru languages and the Bassa and Grebo would not view themselves as being the same people.

In their own territories, the Kru were organised in the way a lot of West African societies were. Each village was essentially self-governing, ran by a council of elders with one among them picked as headman, though loyalties were through the patrilineal line so you might live in one village but be seen as a citizen of another if that's where your father was from. This allowed for close bonds between the different villages, while inter village wars happened, and inter village slave raiding was rampant, there were also open lines of communication. And there were agreed leaders among the headmen, those who held particular influence and authority. A village headman who exceeded his authority and did something to damage the overall order might well find one of these more influential leaders had organised a coalition of villages against him.

In the early 19th Century these Kru leaders were alarmed and wary by the growth of the British settlement of Freetown in Sierra Leone. They saw in it two great dangers. On the one hand, the British threatened to cut them off from the slave trade, their main source of employment. And on the other, the British were taking their land. This was a particular source of alarm because the Kru did not have a concept of land sales. Their land was theirs, they could allow other people to live in it, but that land was sacred to them and would still be theirs. Moreover, Kru leaders had seen the rapid expansion of Freetown and believed, not incorrectly, that any foothold of land taken by the white men and their black settlers would soon be used to take more and more and leave them with nothing.

It is with this attitude that they greeted the first arrivals of the American Colonization Society to Liberia in 1822. The Society was formed as a way of solving America's ethnic strife by simply removing all the Black People back to Africa and thus it was supported by a mixture of slave owners who feared Free Blacks, abolitionists who despised slavery but were against racial mixing and free blacks who chafed under American racism and wanted a chance to build a society with themselves at the top. The majority of African Americans opposed it as ethnic cleansing but enough were desperate enough that thousands got on a boat and headed back to Africa. But the people who picked the destinations and planned the settlements were white and generally quite ignorant about African Politics.

Liberia was not the destination the ACS had in mind, they sent several thousand men to Haiti and, as mentioned in the last article, had initially tried to form a settlement in Sherbro, Sierra Leone. That settlement had been built on land already bought before the voyage had started. The ACS had reached out to John Kizell, an ex-slave who had been captured in Sherbro, taken to South Carolina, freed by the British and was now back in Sherbro. He was sympathetic to other black slaves wanting to return home and had ceded them land and built huts ready for the arrival of the black settlers.

Unfortunately he was neither popular nor powerful among his own people and so his land was mostly swamp. The black settlers died of diseases and starvation and their neighbours, both the British and the native Africans, were happy to let them do so rather than see them grow into threats to their own power. The settlers soon abandoned this site, some went to Freetown and the rest mostly headed east into modern day Liberia where no such agreements had been made.

The Liberian Kru were, of course, aware of this disaster and seem to have viewed it with a mixture of amusement and alarm, they make snide references to it in their negotiations with the white navy officers who came to them asking for land for the settlement that eventually became Monrovia. These negotiations lasted days and do not seem to have gone entirely smoothly, at one point Robert Stockton held Zolu Duma at gunpoint so he could make his point more forcefully. But in the end, at a meeting without weapons, an agreement was reached. Zolu Duma, in return for a great deal of goods from the US navy ship, would let the black settlers settle in his land.

Except as soon as he did that, the other village headmen among the Kru rejected that deal as being dangerous and quickly gathered their forces with the aim of killing Duma and expelling the settlers. But the Kru weren’t the only people in Liberia.

The Mande speaking people were the descendants of the subjects of the Mali Empire and had pushed south in wake of its collapse, setting up in Inland villages where they hacked away enough of the jungle to plant rice and cassawa in their farms. Their social structure was far more rigid than the Kru thanks to the poro and sande secret societies which men and women are initiated into at puberty and which teach fixed social roles.

The most powerful of the Mande in 1822 was Sao Boso of Bopulu who had spent his youth as a petty officer aboard British ships and so was often known by his nickname ‘Boatswain’. He was a man of no chiefly lineage who had taken to state building with a vengeance and who had established what is known as the Kondo Federation, an alliance of villages subservient to him that spread across modern Liberia in a way that was unprecedented. He was the closest thing to a genuine King that Liberia has ever had.

Boso was in favour of a colony happening. He came down to meet the new arrivals and the Kru headmen with an entourage of 200 soldiers and 20 wives. There he declared grandly that in the history of this coast there had never been war between the black man and the white man, only trade. He was not willing to risk that trade by allowing a war and so he bullied the Kru headmen into backing down. The goods given to Zolo Duma were returned so that he would get no advantage against his rivals but the black colony was allowed to be established. Monrovia was founded.

On the surface there’s no reason why this would last any longer than the settlement on Sherbro had. Disease was still a deadly threat, it’s estimated 60% of the colonists died within the first ten years, the climate was hostile, the neighbours unfriendly and they still would have to clear huge areas of jungle and protect them from the elements in order to grow crops and so feed themselves. One of the white agents, Eli Ayres, openly argued for the colonists to give up and settle in Freetown with the British but the African Americans were more determined. They weren’t willing to just swap American domination for British when they had a chance of their own country. It would be a tough road ahead but the colonists were here now and they weren’t going to leave.

The Kru, by all accounts, were aware of this and they discounted their promises to Boso as soon as his soldiers had left. Their headmen were divided between those, such as Zolo Duma, who wanted to welcome the newcomers into their society as a new village and intermarry with them, and those who still viewed them as a threat, strangers eager for land and who were opposed to the slave trade which made the Kru rich. The latter side won out and within months of the colony being established, hundreds of Kru warriors stormed the colonist’s village in an unprovoked attack.

This was the first, but not the last, instance of the native Liberians and the black colonists coming to blows rather than integrating but it is difficult to see Zolo Duma’s idealistic dream ever being realistic. The nature of the settlers was that they wanted to form their own society, not integrate into an existing one based on selling slaves. The settlers were innately hostile to the Kru’s livelihood, as they would prove in the following decades through their bloody efforts to drive off illegal slavers from their coastline.

In those early encounters, the Kru, unlike many people faced with settler colonies, had a chance of winning. The ACS were not government backed, if the colony was destroyed then the plan would likely be abandoned. The Kru had less guns and worse cannons than the settlers but more numbers, and the settlers had limited ammunition. The only reason the settlers survived that first battle was the Kru lost discipline and started looting before they’d properly broken the defenders.

Would the Kru have wiped out the colonists entirely had they won? Probably not, some would have been killed or made slaves again but others might have been adopted into Kru villages and their knowledge absorbed instead and some might have even been allowed to leave peacefully. When the Kru took eight children from the colonists as hostages, they treat them with notable kindness and tenderness, even asking, in their ransom note, what food they were used to and letting them go unharmed in the end despite the ransom not being paid. They were opposed to the colonists but they did not hate them, not yet anyway.

But the Kru didn’t win, the settlers did and, firmly established as in control of their land and building their own Wild West style new town, they began to chafe at the white agents of the ACS. In the early years the colony was not self-sufficient, it was reliant on funds and food bought in by ships from the USA, and would starve if they did not arrive. They could not, yet, cut the apron strings entirely but they were now blooded veterans of war who were not in the mood to be pushed around. An attempt to put them on half rations led to a mutiny and then an agreement that the day to day running of the colony, such as the handing out of rations, would be ran by an elected council of the black colonists, though a white agent would still maintain overall control.

And more black colonists were arriving every year. For the first decade of the colony this was about half educated free blacks and half newly freed slaves. However, once the news of the awful death rate to diseases, the highest recorded anywhere, began to spread, despite the best attempts of the ACS to hide it from new colonists, the former stopped coming and the new arrivals were overwhelming the latter and thus generally in poor health, uneducated and illiterate. The result was that colony was growing increasingly segregated between the richer first families and the much poorer new comers, who often lived in slum housing, 10 to a hut.

The new colonists only got free food from the colony for the first six months, which they often spent ill or adjusting to the climate, and then they would have to work the public farms for money in order to eat, thus giving them no time to train for other occupations. In order to try and improve their fortunes, it was clear more land needed to be cleared for farming but it was a slow and difficult business and the settlers pushed out further into new lands to try and find better soil. The other residents of Liberia were rapidly finding Monrovians expanding everywhere and not just in terms of land. The best way to make money in Monrovia was to sell palm oil to the Europeans and tobacco to the Mande. In short the traders among the Kru found their role as middlemen was being undercut by the newcomers. It is no wonder that more and more of them were forced to ‘suckle off the white people’ to make a living.

The Kru attempted to respond to having their economies destroyed by boycotting trade with the colonies in the hope of starving them out (the colonies had improved their agricultural output but still were reliant on trade to avoid starvation), but when this happened the colonists responded with violence and their words were backed by artillery. The settler’s military advantages meant they could dictate economic terms, and they used that ruthlessly. It was the same story of any settler colony. Farms would be built in new land, those farms would be raided by the people who already lived there, a punitive campaign would be raised in retaliation and then the village of native Africans responsible would be destroyed. The people from that village would then move inland looking for their own land and get into conflict with other villages. It was this new series of wars that collapsed the Kondo Federation. The only difference this time was it was black settlers responsible. Though, it is worth noting at this point that the Kru used the word ‘kri’ to refer to the black settlers and that had been the word they had previously used for white slave traders and ship's captains. And, like they had with the original kri, they began to take jobs in Monrovia and started sending their children to settler schools.

The Kru by the mid-19th century were firmly impoverished, the settlers had all but ended the slave trade, had taken most of the best land and kick-started a series of wars which saw whole villages burnt out. The Krumen who worked miserable jobs for poor pay in British Lagos emerged from this environment and the same factors saw the richer merchants of Monrovia employ dozens of Kru servants who they paid low wages to and, it is often said, beat like slaves. In 1822 the Kru and the settlers had been equals, with both sides respecting the judgment of the Mande. 25 years later, in 1847, the settlers were firmly in control and they viewed both the Kru and the Mande as beneath them, letters from the Liberian settlers about them are often shocking in their racism.

1847 was an important year for Liberia because it was the year they finally won full independence from the ACS and began to truly run their own affairs. The white agents had often been petty dictators, overruling the settlers’ councils and launching wars of conquest in the interior to gain their own power. Of more concern to the Liberian elite, they also maintained control of the port regulations in terms of tariffs and so allowed the society’s directors to maintain a control of the trade that the Liberians could not try to cut out. The first President of Liberia, Joseph Jenkins Roberts was a man deemed black by American racial laws despite only having one black great-grandfather and seven white ones. He was also a trader who made his fortune as a middle man buying goods deep inland in Africa and then shipping them across the Atlantic to buyers. Politically and economically the Society was in his way and as their money dried up they could no longer oppose him. He became the first Black Governor and then, upon independence, its first President.

Roberts was a member of a fair skinned rich aristocracy who were inter-married with each other and lived lives of genuine opulence while keeping a tight grip on all civic and political power. In particular he was the Grand Master of the Masonic Lodge and only members of the Masons held any power in Liberia. And they used this influence to cut-out anyone apart from themselves from the Liberian Trade, Roberts’ brother in law had a complete monopoly on tobacco for instance. To an extent the aristocracy were more American than the Americans, they wanted desperately to prove themselves civilised by the standards of the west, because they had spent their lives being told they weren’t. They took their pride in these trappings of western civilisation, Christianity, clothes, material goods, speaking English etc., to extremes.

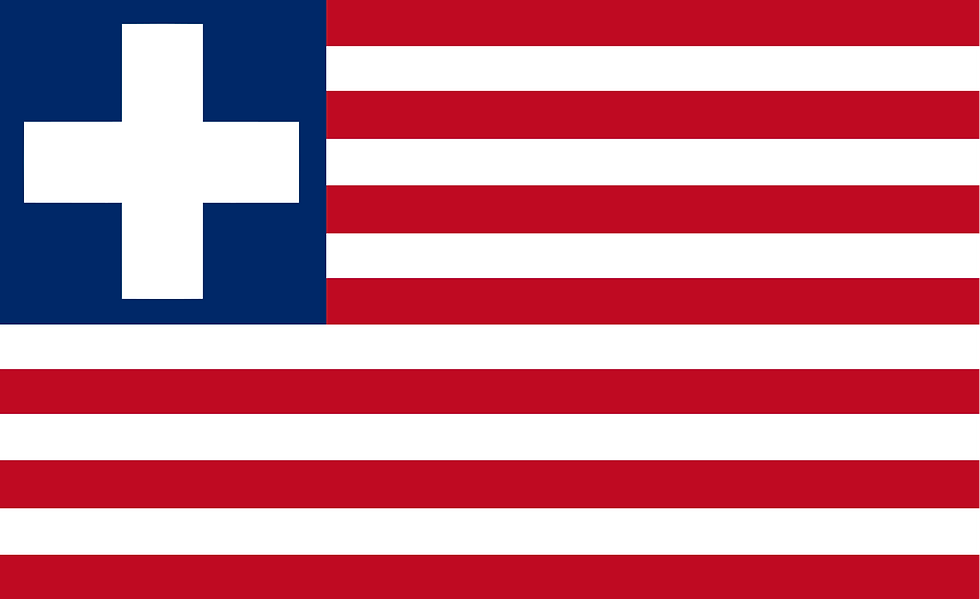

Thus when they wrote their new constitution, they wrote it as Americans. In the preamble to their Declaration of Independence they said “We, the people of the Republic of Liberia, were originally inhabitants of the United States of North America.” Except the vast majority of the people of Liberia simply hadn’t been. The Settlers had won self-rule and their constitution would give citizenship only to people of colour but they would not extend that self-rule to the non-settler peoples of Liberia. Roberts doesn’t seem to have even considered it.

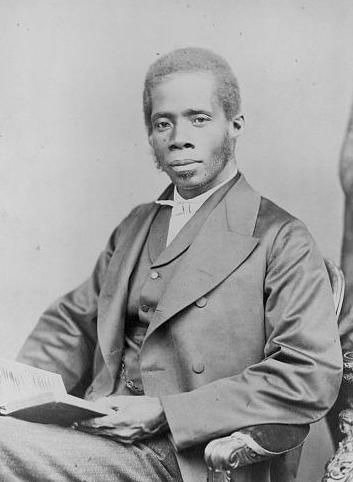

But it did occur to what would become the opposition. In particular it became a passion of Edward Wilmot Blyden, one of Liberia’s greatest thinkers and a man who had a vision for the republic that was closer to Zolo Duma’s than Roberts’. Blyden was born free rather than a slave and so had most of the advantages in education and money that the rest of the Republic’s leaders did, but he was black rather than mixed race and viewed Roberts and his supporters with a contempt that quickly became racist. The mixed raced elite were in his mind obsessed with white society and contemptuous of black people and so had chosen the wrong path. The future of Liberia, for Blyden, was in the interior not ocean trade.

At first he seems to have envisioned conquest and then integration, Liberians marching through Western Africa and annexing nearly polities by force. But while serving as a soldier in a border war with the Mande, he grew to respect them. They were Muslim not pagan and not only were literate but had in fact invented their own alphabet. These were not the slave trading savages he had imagined but a society he liked a great deal more than he liked Monrovia with communal property preventing similar levels of inequality. Roberts would not extend the vote to the non-settlers because they were so numerous that they would quickly dominate politics and make a state to their liking. His compromise was that the vote was extended only to those who had been adopted by the settlers as wards and so had been raised with Monrovian values. But to Blyden the fact that the Mande didn’t have Monrovian values was the appeal, he wanted to extend the vote in order to force Monrovia to integrate into the existing Liberian norms rather than keep their own. His dream was essentially that of a new Kondo Federation only with an elected President rather than a King in the centre.

This is unlikely to ever happen. There simply wasn’t enough good will on either side for them to want to be tied together that closely. The settlers would be worried about the Mande voting to relegalise the slave trade and the Mande about whether the better armed settlers could accept losing elections peacefully. But it could have been a starting point of a governments plan, an aim. If an attempt at a settlement had been made then it’s possible some kind of arrangement could be reached, between Blyden’s vision and Roberts' that gave a way for the residents of Liberia to live amongst each other.

Certainly a lot of people weren’t happy with the status quo. The small entrenched elite dominated trade and politics to the extent that they had blocked any route out of poverty. Blyden was a trained tailor but soon discovered that the rich bought their clothes directly from Paris and the poor couldn’t afford customised clothes. What was lacking was a middle class and therefore voters who had benefited from the existing rule.

In the 1869 Presidential election, the ruling Republican party lost and were replaced by the True Whigs, the party of the Monrovian poor and the up-country farmers, the party that Blyden had helped form. It had campaigned on overthrowing the old elite and extending the franchise.

It had also campaigned on funding Liberian schools throughout the interior and creating a central bank. To fund this the new President, Edward Roye, borrowed 250,000 pounds from London Banks. The British, in classic colonial style, charged extortionate interest on this debt, the Liberians would end up having to pay back 650,000 pounds, and used that debt to bully the Liberians in diplomatic negotiations. This would be the first of many such loans but the most impactful of all of them.

The old Elite, having never accepted Roye as President, jumped on the loan terms loudly as being proof of his unsuitability to rule. Soon open violence erupted, Roye was arrested and then shot trying to escape and Roberts retook his position as President. But this was only a brief return to power for the Republicans, the populist True Whigs had replaced them and were soon to become the natural ruling party. But the True Whigs also became less radical. Roye had proved that they didn’t need extended suffrage to win and as they reduced inequality and intermarried into the existing elite, the result was that the Monrovian settlers formed a united front as Americoes against the non-settlers, rather than Blyden’s hoped for popular front of poor settlers and natives against the elite. Had Roye been cannier and luckier that could have been avoided.

The last three decades of the 19th century were tough ones for Liberia. The government was hampered by its ever increasing foreign debt and increasingly corrupt, with bribery and embezzlement rampant. And inequality was mainly reduced by the rich getting poorer rather than the other way around. The elite traders found themselves losing their main advantage of being able to sell goods from the African interior in Europe and USA without middlemen by the growth of colonial empires that could do the same on a much bigger scale. And those colonial empires were also on the prowl.

Liberia in 1869 claimed to rule 180,000 square miles of territory but by 1900 that was only 43,000 square miles. The rest was seized by France, in three different treaties, and the UK, in one. This was only land the Liberians claimed but hadn’t either settled or conquered yet but there were dangers beyond that. Germany, in 1898, sent a gunship to Monrovia with plans to take control of the entire Liberian Republic and only backed down when the British took the Liberian side.

In 1911, Britain would turn back from Sheepdog into Wolf. They had long wanted, and been refused, permission for the British West African army to cross over from Sierra Leone in pursuit of rebels. Instead they demanded that Liberia fund a frontier force to control their own borders and strongly hinted that the proper leader for it was Mackey Cadall, a white British civilian living in Monrovia. Cadall was appointed to this by the President and then went out to the border and recruited this army, which later turned out to be actually made up of British soldiers from Sierra Leone who had crossed the border secretly. Cadall also took control of local taxation to fund it and forced the existing police forces to obey his orders. The British had not only got their army over the border but also forced the Liberian government to pay their wages. When President Barclay discovered this and tried to cut off their access to tax money, the soldiers attempted to storm the capital and had to be disarmed by the Liberian militias and escorted back to Sierra Leone. The Frontier Force was then reorganised under the command of Black Buffalo Soldiers on loan from the US army in case the West African Army would attempt another invasion.

But they didn't, Liberia survived all the aggression of the scramble as an independent state. It was the only country with an African capital to do so, helped by the way that they acted as a buffer between the British and the French and that the Americans had some small interest in their survival. But imperialism still happened, just by the Americoes rather than Europeans. In order to prove that they had full control over the land, and so prevent further annexation, the Liberians needed to formalise their relationship in the interior. And that relationship became formalised as indirect rule. A hinterland administration was set up in which the prominent chiefs maintained control alongside government commissioners there to make sure the chiefs obeyed Monrovian interests.

All of the worst abuses of colonial states were reproduced by the Americoes in this hinterland. Rapes, arbitrary punishments and taxes, massacres, economic servitude and forced labour were rampant and even the unforgivable sin within Liberia, participation in the slave trade, happened. Domestic slaves had remained in some areas of the hinterland and greedy commissioners would demand use of these as labourers instead of taxes from village headmen and then those slaves were sold as cheap labour to Spanish and Portuguese colonies where the conditions were dreadful. The government commissioners were generally brutal and corrupt, the only perk of the position was the chance to try and gain a personal fortune through illicit means, and had little oversight. Even if caught they were rarely punished, thanks to a court system that placed little value on the inhabitants of the hinterland and a civic system that was firmly focused on Monrovia. The natives fought back by forming secret societies that captured Liberian officers and ritually sacrificed them in secret ceremonies. It was soon obvious to visitors to the country that the situation wasn't sustainable.

New Arrivals to Liberia had basically stopped after the 1870s but come the 1920s a new ‘Back to Africa’ movement began only this time led by Black Radicals rather than White Elites. Liberia was an obvious destination. Marcus Garvey, its Jamaican leader, was sought out by the Liberian Government hopeful of attracting new immigrants and investment. Garvey sent his Haitian compatriot, Elle Garcia, to Monrovia to fact find. Garcia's report back was that the country was one in which a weak and relatively powerless elite held power and used it to discriminate against and abuse the majority. He recommended that Garvey take the Liberians up on their offer as, by making alliance with the disenfranchised majority, they’d soon be able to control that government and send Liberia in a more radical direction.

The problem was the USA thought that might be true too and were determined to avoid it. President Harding of the United States met President King of Liberia in 1921 and after advising him not to make alliance with Garvey, urged congress to approve a loan of 5 million dollars to King's government. Later that year the FBI arrested Marcus Garvey for mail fraud and passed on Garcia’s report and its recommendations to King. King, scared of alienating the USA, took the hint, he distanced himself from Garvey and uninvited the back to Africa movement from his Republic. Despite this however in 1922 the US Senate voted against the loan. King had rejected Garvey only to get nothing from Harding. But, in case King was to change his mind, London, and Paris, scared of Garvey’s radicalism made it clear that they too wanted Monrovia to distance itself from the Back to Africa movement. Yet again Monrovia gave in, a second attempt by Garvey to make a deal was rebuffed, instead they sold themselves to an American tyre Company who took essential control of the country’s economy and treasury much like United Fruit had done in Central America.

Time and time again, radicals understood that Liberia could only be strong with the Americoes and the non-settlers working together. And time and time again, the radicals were rejected by an elite worried about losing their security if they did so, either by being outvoted by the majority or being overthrown by annoyed western powers. Liberia was never a racially apartheid state, Kru or Mande wards of the Americoes became full citizens and were integrated, but there was a cultural apartheid, blood lines were less important that acting like a settler. If you were not a Mason and you did not live in Monrovia and you did not act like an Americoe you would achieve little. The cause of Blyden and Garvey, in terms of opposing that cultural elite, would be taken up the People’s Party, the Reformation Party and finally the Progressive Alliance but, with elections now routinely rigged by the True Whigs and Opposition parties denied ballot access and harassed physically, they made no progress. Instead the True Whigs, and the Americoe elite they represented, maintained control up until 1980, where they were overthrown in a bloody coup and minority rule government was ended once and for all, to be replaced by instability and civil war.

It did not have to end that way but there are only so many times you can turn down the chance for reform before the choice gets taken from you.

Of course Liberia also did not have to ever form, the settlement had plenty of chances to be ended prematurely. In that scenario what would have happened to the Kru and the emerging Kondo Federation? Well, we can perhaps get some insight into that by what did happen to similar societies elsewhere on the slave coast, in Ghana, Benin and Nigeria.

Comments