Microfiction from the SLP Community: Part 5

- Sea Lion Press

- Mar 20, 2023

- 7 min read

By Gary Oswald, Ishan Sharma and Lilith Roberts

One of the most common forms of microfiction you find on AH forums is the wikibox, an edited infobox from a wikipedia page. This can be a battle, a war, an election, a movie, a country etc. Take the below instance for example, where it is a chamber of congress.

It's classic micro-fiction in that its says very little, but implies a great deal more about how we could have reached this situation.

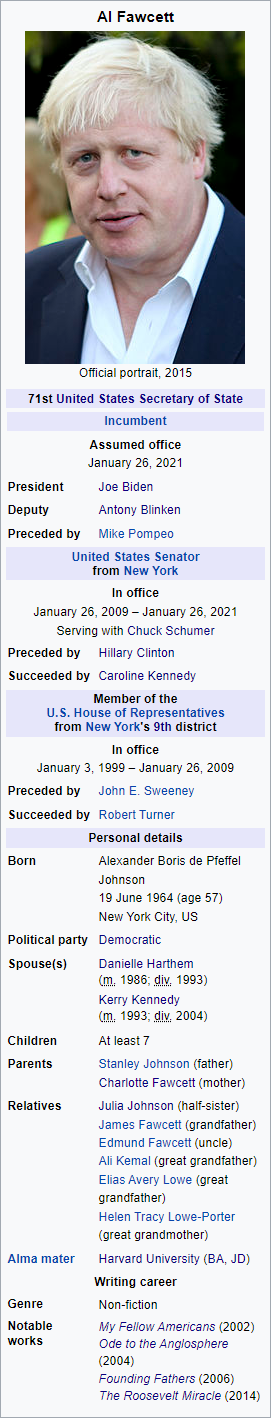

Likewise there is the following by Lilith C.J. Roberts which reimagines a current political figure in a different context.

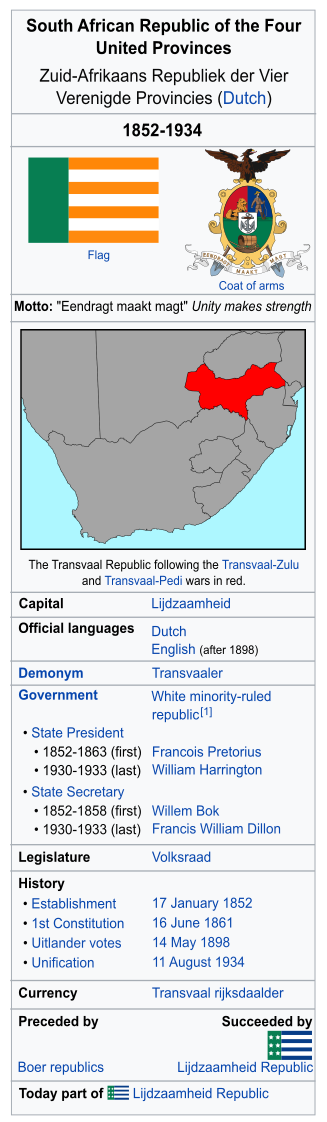

Of course, much like lists or maps, wikiboxes often come as part of a timeline or with writes ups attached. Such as the following by Ishan Sharma.

"The Transvaal Republic was a Boer, later Anglophone, republic east of the Vaal River, which existed from 1852 to 1934.

Boers first moved into the area as trekboeren looking for further land in the eighteenth century, but this flow only became sizeable following the Dutch Cape Colony's reforms of the nineteenth century. The Dutch government, influenced by the Enlightenment, proved hostile to settler interests, disarming them, prohibiting expansion, centralizing the administration, and banning slavery, all factors which led boeren to rebel against the government, and when this was crushed in the 1840s they moved across the Orange River; with the region going through massive ethnic movements due to Shaka Zulu's expansion and the disarray of the mfecane, they were able to establish an independent republic, however, it was one which was swiftly conquered by the Dutch army. Settlers subsequently moved further beyond the Vaal River, and the Dutch were opposed to further expansion. Instead they signed a treaty with the settlers beyond the Vaal, releasing them from citizenship and establishing their independence as a buffer state.

When these settlers entered the region, it was already going through chaos. A Zulu army led by Shaka's lieutenant Mzilikazi broke from the Zulu nation overall and established a state in the region using Zulu military tactics, causing heavy chaos and warfare in the region. When the boer settlers came, they subsequently were able to counter Mzilikazi's attacks with their guns, forcing him to migrate north where he would found the kingdom of Mthwakazi. With the region in disarray, the Boers then established a series of republics around new towns. Francois Pretorius, the State President of the centrally-located republic of Lijdzaamheid, sought to unify these republics, and after a series of complicated wars and agreements with other Boer republics, he established the first constitution of the Transvaal Republic by the 1860s. This republic was marked by a rejection of the Enlightenment ideals followed by the "godless" Hollanders.

As such, like an old oligarchical republic, citizenship was only extended to the (white) elite, old-fashioned honorifics were used rather than the French Revolution-inspired address of "citizen" dominant in the Netherlands, and the Dutch Reformed Church was made the only legal religion without authorization. Nevertheless, it immediately began with a program of state-building. It minted its own rijksdaalder for currency, gave itself a flag reminiscent of the old oligarchical and quasi-monarchist Dutch Republic overthrown by the Batavian Revolution, and the State President travelled in circuit around the republic like a medieval king. To avoid dependency between either the Dutch in the Cape or the British in Natal, an agreement was made with the Portuguese to establish a road to the port of Lourenço Marques. Beyond that, the Transvaal immediately initiated wars with native kingdoms, with the Pedi to its north and the Ngwane peoples to its southeast. However, here it faced issues. Slowly, the Pedi adjusted their tactics to Boer guns, and under their King Sekoekoeni I, they began to go on the offensive. In 1877, the Transvaal seemingly teetered on defeat. This already bad situation got worse when the Zulu kingdom to the Transvaal's south declared war. With the Transvaal government fearful of Zulu troops in Lijdzaamheid, it immediately sued for peace with the Pedi, recognizing their independence and giving up the Zoutpansberg region. This was not enough to stop the Zulu onslaught, however, and as the Zulu armies marched north, the party calling for peace strengthened, and finally in 1880, it sued for peace with the Zulu, ceding large amounts of the Transvaal to them.

This Transvaal, teetering on collapse, frantically attempted to centralize and modernize its administration, to prevent further defeat. But this got worse when, in 1886, gold was discovered in the Witwatersrand region of the Transvaal. News of this spread across southern Africa and indeed beyond. The result was a great wave of prospectors and miners, looking for gold. The new town of Goudfontein emerged near the site of the gold discovery. While people from around the world moved to the Transvaal for gold, most of them came from British Natal, or from other English-speaking countries. They bristled at the sole legality of the Dutch language, of the Dutch Reformed Church. And the Transvaal government quickly noted that, at the rate of immigration, uitlander migrants, and English speakers, would make a majority of the white population in the near future. And so the domicile requirements for citizenship were immediately lengthened to fourteen years, and the English language was banned with children forced to go to Dutch schools - or more precisely, in the irregular rustic taal of the Boers. Beyond that, the Transvaal created a new class of randheeren who exploited the gold rush. Some of them were Dutch, having already tapped into the Paulustad diamond rush, but most of them were English-speaking - from Britain, the United States, and Australia. And this new class hated their exclusion from the halls of the Republic, forming the Goudfontein Reform League to petition for suffrage expansion. The Transvaal Republic would attempt to close off immigration, they built a railway with the now-French port of Lourenço Marques to avoid dependence on Natalian ports, but to no avail. In 1891, the Transvaal government established a municipal administration in the Witwatersrand elected by uitlanders in an attempt to satisfy demands for reform. Yet, they continued, and in 1896, the government of the Witwatersrand declared the abrogation of the Transvaal constitution and declared their desires to march on Lijdzaamheid to force a new one which would expand suffrage to all white people. This caused a brief civil war; under the new constitution of 1898 which ended it, citizenship requirements were relaxed and the Transvaal was decentralized between four provinces - Witwatersrand, Lijdzamheid, Uysberg, and Zuid-Nassau - to avoid Anglophone domination of all sectors of government. Stability was achieved.

And this changed everything. While many Britons recognized that the Transvaal had become the new centre of the region and advocated its annexation, they would be surprised at the extent of it. British Natal became a mere dependency and its economy was driven by its use as a Transvaal Port; likewise with French Lourenço Marques. In 1905, Transvaal, British Natal, and French Lourenço Marques signed a customs agreement establishing common institutions to ease trade. British beliefs that the Anglophone Transvaalers now dominant would look to them proved wrong when, instead, they proved far more independent-minded. The state scrapped the medievalism dominant in the past, and became a modernizing white supremacist state. Thus emerged the Transvaal of the early twentieth century, the beating heart of white southern Africa, dominated by a class of randheeren which ruled over a white elite, with black people wholly disenfranchised. But the white miners of the Witwatersrand resented this domination. They hated the randheeren with a passion; but they also hated black labour, regarding them as an economic threat. Thus, white supremacist labour unions emerged, and though racially inclusive labour unions also emerged they weren't large enough. In 1922, when the randheeren attempted to employ cheaper black labour in gold mines, the result was a wave of strikes among white workers. These strikes were brutally suppressed, but this was hotly opposed, and in the 1924 Transvaal elections, the Labour Party won a majority of seats in the volksraad and took control of the State Presidency.

And with that they established a white peoples' associationist state. They established welfare programs for white people and ensured that the mines would be dominated by white people, not by black labour. They attempted to sponsor white supremacist labour activity in other parts of south Africa, but this failed; in the Cape, labour evolved on racially egalitarian lines and likewise in Natal, while in French Lourenço Marques labour almost entirely consisted of Tamil and Javanese indentured servitude. They also served to alienate neighbours; the constitutionalist movement in the Zulu Empire regarded the Transvaal as synonymous with tyranny, while the conservative Boers who made a majority of white people in French Lourenço Marques looked down at the dominance of rough Anglophone workers. In Natal, the mixed-race and Indian populations in particular hated Transvaal white supremacy, and similarly, in the Dutch Cape, the Transvaal was viewed as the antithesis to its liberal franchise. The result was that, in 1929, the Labour Party was defeated in no small part due to the alienation of its neighbours. The victors, an alliance of Boers and middle-class Anglophones, sought to prevent them from taking over again. Accepting much of the labour legislation, they nevertheless sought to enfranchise upper-class black people if only to stop the Labour Party from coming back. By the new Native Rights Resolution of the Volksraad, those black people who could read and write Dutch or English and passed a property requirement could now vote. More revolutionary, however, was the municipal legislation. Black municipal governments were established, with power over black neighbourhoods. This was more an attempt to satisfy the growing movement for racial equality than anything else. And ultimately these measures of small racial inclusivism, intended to strengthen white supremacy, would fail as instead black people used these opportunities to force racial issues to a head through the tactics of obstructionism and oppositionism; the dispute over racial equality was only strengthened by these reforms. But at the time, seemingly more important was the discussion of union between the Transvaal, British Natal, and French Lourenço Marques. The strong economic ties between them resulted in there already being talk of it, and the Transvaal government quickly forced the issue in the Customs Union assembly. In 1931, it forced through the creation of a popularly elected Customs Union Assembly, and after unionist victories in Natalian and Laurentien elections, both France and Britain were ultimately forced to the negotiating table. As part of the agreements for union, the federal Transvaal system was extended to Natal and Lourenço Marques, and both France and Britain would retain basing rights as well as offshore islands. And so, in 1934, the Transvaal Republic was dissolved and replaced by the Lijdzaamheid Republic."

In that case, the write up is extensive enough that the microfiction is less of a wikibox and more of a wikipedia page, an excerpt from an encyclopaedia in that format.

Or alternatively, wikiboxes can be strung together to form a mosaic of related images like the example below.

留言